craft review by Becky Levine

It’s fiction. We can write pretty much anything you want, right? We’re making up the story, we’re creating the world, and what we put into that world is up to us. There’s just one challenge.

Our readers have to believe it.

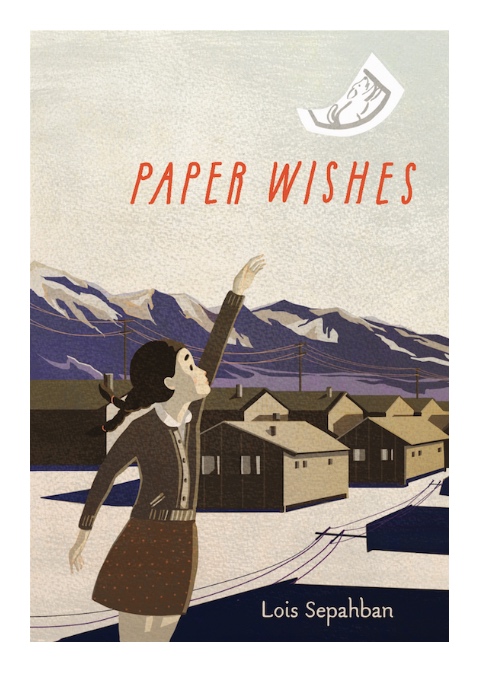

In Lois Sephaban’s Paper Wishes, Manami and her family are forced to leave their home in the Pacific Northwest during World War II and move to an internment camp in the hot, dry desert. They live in horrible conditions, are treated like the enemy, and face challenge after challenge. And, in the midst of this, without any physical injury or illness, Manami literally loses her voice.

Sepahban weaves in Manami’s lost voice gently, without making it feel out of balance with other story threads. She also, however, uses several specific techniques to ensure that Manami’s inability to speak is believable.

Giving Each Character Their Own Response

One of the most important things Sepahban does is to make sure that not only Manami, but each character in the story has a distinct response to being put in the camp. Father and Mother keep themselves busy. Grandfather withdraws, sits around, and resists eating. Manami’s best friend Kimmi seems almost untouched, but even her undiminished cheerfulness represents her particular reaction. Everyone in the story is an individual, and Manami’s voicelessness is one of many ways in which they deal with what’s been done to them.

Action: Think about the biggest change that happens in your story. How does the main character respond? How do the secondary characters respond? Is each character’s reaction unique and based in who they are?

Another Way to “Speak”

As strong as Manami’s internal narration is, I think I’d have still had a harder time accepting her lost voice if it meant she had no way to communicate to the other characters. Sepahban, however, wisely gives the girl a second communication path—her drawings. Manami’s art allows her to “speak” to her teacher, Miss Rosalie. Through her drawing, she is able to respond to the poetry Miss Rosalie reads.

[Miss Rosalie] reads poems about spring and summer and honeybees and budding flowers. My hand flits over my slate, dipping and bobbing, scratching and resting. Chalk feathers from one line to another, circling and looping until I am finished.

‘Beautiful,’ Miss Rosalie says when she picks up my slate. She bends down to look into my eyes. ‘This is how I picture the seasons changing, too.’

By allowing Manami to communicate and connect with others through her art, Sepahban prevents the loss of Manami’s voice from being awkward or disruptive. The missing voice becomes a seamless and subtle part of the story, one which we accept and believe.

Action: Think about your main character’s abilities, however normal they may seem. Take away one of those abilities. Draft a short scene in which your character can’t use that ability. Now think about a way you could replace the ability with something else. Revise the scene. Have you weakened or strengthened your story?

Connecting Manami’s Voice to the Plot

The most important thing that Sepahban does, I think, is to connect Manami’s voice to the plot arc. At the beginning of the story, Manami is forced to leave behind her dog, Yujiin. In trying to hide Yujiin, Manami stays quiet. When a soldier asks what she is holding, she presses her lips shut and doesn’t answer. Only when Yujiin is taken from her does she make noise—she kicks and screams. Later in the story, Manami thinks that the dry desert air and all the sand must have taken her voice, but Sepahban has already shown us Manami setting herself up for silence, in trying to keep her dog safe.

Midway through their time in the camp, Father brings Manami a new puppy. She has been sending her drawings into the wind, hoping they are wishes that will bring Yujiin back to her. She is terrified that, if she keeps the puppy, Yujiin will stay lost.

I want to explain, but my throat closes tight. Too tight for words to get out. Too tight for air to get in. I run outside to Mother’s garden.

The new puppy goes to Kimmi.

Later, when Manami has moved further along her story arc, when she is more ready for change, another dog comes into her world. A dog that is still not Yujiin, but one that looks like Yujiin and that—also like Yujiin—needs a home. Manami lets Seal into her home and her heart. But she still doesn’t speak. Not until they are leaving the camp, being moved again. Another soldier tries to take Manami’s new dog.

I unbutton my coat and hold Seal’s nose close to mine. He smells of sage and dust. He licks at the tears on my cheeks. I pull him close to my body and our hearts beat against each other.

The cracks in my throat rip wide open.

I remember Miss Rosalie’s words I am brave. I am strong.

‘No!’ I say. ‘No!’

By tying the loss of Manami’s voice, and its return, to major story events–all of which are built on the same problem–Sepahban gives solid reasons for what happens to Manami. She creates a believable “why” behind Manami’s inability to speak for so long and a need for her to regain that ability quickly and finally, at the end of the book.

Action: Identify the biggest emotional change your main character goes through. Now find the three biggest plot points in your story. Are the emotional arc and the plot arc connected at these points? If not, take some notes for your next revision. Think about how you can tie the emotion more closely to the action.

Believable Worldbuilding

If we’re writing about elves and unicorns, we need to build a world in which these creatures can exist. Worldbuilding, however, is just as important in realistic fiction as in fantasy. The best books are specific, with heroes who have a particular problem or a unique personality. We want to push our stories past the everyday, past the usual. And we want our readers to believe in whatever we put on the page, because we have done the work to make it all feel right and true.

Keep an eye out for our Q & A with Lois Sephaban, coming next week!

Becky Levine writes middle-grade novels and picture books. She has written two nonfiction children’s books for Capstone Press and is the author of The Writing & Critique Group Survival Guidefrom Writer’s Digest Books. Becky lives in California’s Santa Cruz mountains and, in her day job, is Foundation Relations Manager at The Tech Museum of Innovation. She also blogs at beckylevine.com.

Becky Levine writes middle-grade novels and picture books. She has written two nonfiction children’s books for Capstone Press and is the author of The Writing & Critique Group Survival Guidefrom Writer’s Digest Books. Becky lives in California’s Santa Cruz mountains and, in her day job, is Foundation Relations Manager at The Tech Museum of Innovation. She also blogs at beckylevine.com.

Kristi Wright

Wonderful post! I love the reminder to have your emotional arc and your major plot points intersect!